When Will I Be Blown Up

An atomic bomb is coming for all knowledge work.

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up?”1 (William Faulkner, 1950)

Just as Faulkner saw the threat of the atomic bomb reshaping human experience, the rise of AGI and advanced AI forces a new existential question: When will I be automated away?

Most of the conversation around AI still assumes that these systems will just make workers more productive and that there will be a slow, gradual shift as new economies develop in response to these advanced technologies. That’s the same story we’ve told ourselves through every technological leap. I think this time the shift will be much faster and more complete.

I think an atomic bomb is coming for all knowledge work.

Anthropic anticipates that powerful AI systems, possessing intellectual capabilities comparable to or exceeding those of Nobel Prize winners across various disciplines, will emerge by late 2026 or early 2027. These systems are expected to autonomously handle complex tasks over extended periods, interact seamlessly with digital interfaces, and control physical equipment through digital connections.

I agree with Michael. Most of the discussions about AI focus on vague claims of increased productivity, but the systems the Anthropic team refer to suggest something much bigger happening. Anthropic is on the “fear-mongering” side of the Great AGI Debate, but 1) I agree with them and 2) at least they’re engaging with important ideas around what is to come and what is to be done.

Right now, there is a lot of hype and excitement from venture capitalists and technologists about how these current AI systems augment the worker and streamline workflows. The software engineer can write more code and faster. This framing assumes a best-case scenario for the worker. Productivity is up and the engineer is happy (and employed). I think we run into a failure of imagination when we assume augmentation is the only outcome.

Expanding our AI discourse

In an article published March 13th, 2025, Vox’s Dylan Matthews writes2:

“Let me offer, then, a thought experiment. Imagine we get to a point — maybe in the next couple years, maybe in 10, maybe in 20 — when AI models can fully substitute for any remote worker. They can write this article better than me, make YouTube videos more popular than Mr. Beast’s, do the work of an army of accountants, and review millions of discovery documents for a multibillion-dollar lawsuit, all in a matter of minutes…How does that reshape the US, and world, economy?”

I think that’s a very worthwhile thought experiment that technologists and policymakers should be spending a lot more time on. Our discourse around AI right now spends too much time in the “known unknowns” quadrant of Donald Rumsfeld’s “awareness” matrix, and I don’t want us winding up doing whatever the equivalent of looking for WMDs in Iraq is when it comes to the AGI debate.

I think we need to push the conversation further and start increasing what we are aware of. There are the technical risks that the labs like to discuss around alignment, safety, and bias, but the real unknown unknowns lie in the murky social, political, and psychological waters. What are the implicit assumptions we’re making when talking about AI? What are the questions we aren’t thinking of to ask?

Most people implicitly assume AI will always need human oversight

We assume AI will make human workers more valuable instead of replacing them

Might capital and labor power structures change in unimaginable ways?

Will AI be deployed in ways humans don’t understand?

What does society look like in total AI abundance?

The future state of these systems is not augmentation, it is replacement.

One example that many friends I’ve spoken to agree with is that the job of an investment banking analyst will be fully automated within 5 years. Microsoft Excel augments one’s ability to do financial analysis, but what about when one is able to click and drag a data room into an AI system that builds you a financial model and formatted pitch deck instantly? Where is the incentive to hire an analyst? The future is not that the analyst can do 10x more work, it’s that the system does all of the work autonomously. Even today, it’s hard to imagine hiring an entry-level data analyst to crank out dashboards, basic Python, and SQL queries when now even a moderately technical PM can get to 95% completion of necessary tasks by using currently available tools.

These technologies will exist within the decade.

Importantly, I don’t believe these changes will be like the industrial revolution where processes slowly get automated and labor reskills/retrains and finds new industries. What’s the hiring market going to look like for the current high school junior who is planning on studying computer science in college? I’m not saying knowledge work won’t exist anymore, but early stage founders I’m meeting are talking about how tools like Cursor already mean they don’t need to hire the incremental junior engineer. At a certain point, the technology is good enough that it autonomously does 99% (or maybe 99.99%) of computer-based tasks. The machines are building the machines, and we, humans, will be doing God knows what. Maybe working less? Doubt it!

Who captures the value of AI

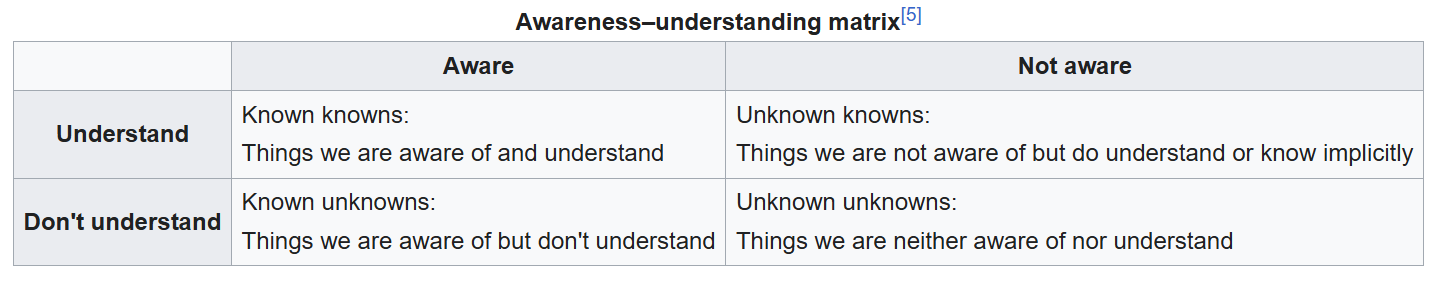

What should coincide with these AI developments is massively increased productivity, but where is the value of this productivity going to accrue if the average knowledge worker’s job is fully automated?

Historically, productivity increases have benefited both labor and capital, but AI’s unique ability to automate knowledge work might tip the scales dramatically in capital’s favor. Wages won’t go up if you don’t have a job!

Our past theories around labor and technology and productivity don’t hold up. I worry that the frameworks we have to talk about these problems are wholly outdated. Take this excerpt from an Economic Policy Institute piece on automation in 20173:

“Studies that attempt to estimate the number of jobs that will be potentially lost to automation in the future never seem to take into account automation’s positive effects on employment,” said Bivens. “The invention of the automobile eliminated jobs in the horse-drawn carriage industry, but it led to new jobs in the repair, and sales of autos, as well as the construction of highways. There is no evidence that future automation will somehow be different.”

Bivens’ argument here is a relic from when we often thought of technology as a tool for labor efficiency, but transformative AI systems will remove the need for human input entirely without creating a new job category. Maybe I’ll end up as my ChatGPT’s butler or something.

I’m an optimistic person, so I think most of us will be okay. At the very least, there is no point in being a doomer about this, but the nature of knowledge work and labor is about to change in ways we aren’t prepared for. The safety net that existed for college-educated-white-collar workers is looking a bit rickety from here. The question is no longer if AI will automate certain roles but how quickly and how completely it will do so and what is going to happen to society in the wake of these changes.

So to you (us) educated-laptop-job-elites, don’t ask for whom the labor revolution bell tolls.

It tolls for thee.

William Faulkner, Nobel Banquet Speech, December 10, 1950, Stockholm, Sweden, The Nobel Prize, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1949/faulkner/speech/.

Dylan Matthews, "AI Is Coming for the Laptop Class," Vox, March 13, 2025, https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/403708/artificial-intelligence-robots-jobs-employment-remote-workers.

Lawrence Mishel and Josh Bivens, "No Evidence That Automation Leads to Joblessness or Inequality," Economic Policy Institute, May 24, 2017, https://www.epi.org/press/no-evidence-that-automation-leads-to-joblessness-or-inequality/.